|

by Salah Zaimeche BA, MA, PhD

FSTC Limited

July 2002

from

MuslimHeritage Website

Introduction

The Turkish navy are famous for their endless battles fought for

Islam, from around the late eleventh

century to the twentieth, from the most further western parts of the

Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean

and the Straight of Hormuz.1 There is, however, another aspect of

Turkish naval activity, that is their

contribution to the wider subject of geography and nautical science.

This aspect, however, like much else of

Islamic science has been completely set aside. Hess puts it that

European historians were only preoccupied

with the identification of their own history. They first unravelled

‘the dramatic story of the oceanic

voyages,' their discoveries, and their commercial and colonial

empires, and only stopped to consider how

Muslim actions influenced the course of European history.

Once such

questions were answered, the study

of Islamic history became the task of small, specialized

disciplines, such as Oriental studies, which occupied

a position in the periphery of the Western historical profession.2

And the successful imperial expansion of

Western states in Islamic territories during the late nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries, Hess adds,

‘confirmed for most Europeans the idea that the history of Islam,

let alone the deeds of Ottoman sultans,

had little influence on the expansion of the West..3

Although Hess observes one or two improvements

by the time he was writing, the picture was still the

same as nearly a decade later after him, Brice and Imber in a note addressed to the Geographical

Journal, observed that although European charts of

the Mediterranean have received much focus, none

has seriously considered similar Turkish maps.4 Even

worse, European scholars have dismissed Turkish

works as being of Italian origin imported into the

Ottoman Empire, or the work of Italian renegades,

which Brice and Imber went on to demonstrate was

without any foundation of veracity.5

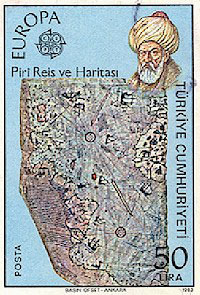

Turkish nautical science was much in advance of its

time, though. Hess notes that in 1517 Piri Reis

presented his famous map of the New World to the

Sultan, giving the Ottomans, well before many

European rulers, an accurate description of the

American discoveries as well as details about the

circumnavigation of Africa.6 Salman Reis, a year

later, added more onto that. Goodrich, in

a

pioneering work,7 also went a long way to correct

the overall impression, giving excellent accounts of

the Ottoman descriptions of the New World as it

was then being discovered in all its strangeness,

variety and richness.

Amidst the Turkish men of the sea of great repute, Piri Reis is by

far the one with the greatest legacy. There are two entries on him

in the Encyclopaedia of Islam. The first by F. Babinger 8 and the

second by Soucek.9 By far, Soucek's entry is much richer, more

informative and competently written. That of Barbinger, also

out-dated, still offers a good variety of notes of primary sources

likely to serve a devotee or researcher.

There is a further entry on Piri Reis in the Dictionary of

Scientific Biography by Tekeli.10

Piri Reis - the Naval Commander

Piri Reis was born towards 1465 in Gallipoli. He began his maritime

life under the command of his, then,

illustrious uncle, Kemal Reis toward the end of the fifteenth and

early centuries. He fought many naval

battles alongside his uncle, and later also served under Khair eddin

Barbarossa.

Eventually, he led the

Ottoman fleet fighting the Portuguese in the Red Sea and Indian

Ocean. In between his wars, he retired to

Gallipoli to devise a first World map, in 1513, then his two

versions of Kitab I-Bahriye (1521 and 1526), and

then his second World Map in 1528-29. Mystery surrounds his long

silence from between 1528, when he

made the second of the two maps, and his re-appearing in the mid

16th as a captain of the Ottoman fleet in

the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.11

The World Maps

Piri Reis's first World Map in 1513, of which only one fragment is

left shows the Atlantic with the adjacent

coasts of Europe, Africa and the New World. The second World map

from 1528-29, of which about one

sixth has survived, covers the north western part of the Atlantic,

and the New World from Venezuela to

New Found Land as well as the southern tip of Greenland.

The

fragment of the first World map discovered

in 1929 at the Topkapi Museum palace, signed by Piri Reis, and dated

Muharram 919 (9 March-7 April

1513) is only part of the world of the map which the author handed

over to the Sultan Selim in Cairo in the

year 1517. The German scholar, P. Kahle, had made a thorough

analysis and description of it12, observing

that Piri Reis was an excellent and reliable cartographer.

Kahle

also points out that the whole picture of

Columbus has been distorted, as nearly all the important documents

related to him, and in particular his ship's journal, have been preserved not in their original but in

abstracts and edited works, mostly by Bishop

Las Casas.13 Long after Kahle, in the mid 1960s, Hapgood returned to

the subject of the Topkapi map,14 but

amazed by the richness of the map, and so convinced he was that

Muslim cartography was poor, he

attributed it to an advanced civilization dating from the ice age.15

Hapgood's position seems now to edge on

the ridiculous, not just for its exuberant assertions, and his

stretching of evidence to beyond the fictional,

but also in view of recent works on the history of mapping. The

recent voluminous work by Harley and

Woodward, by far the best on the subject, shows in rich detail, the

meritorious role of Muslim cartography

and nautical science.16

As for Kahle's original find, one regret he

expresses, was that the fragment found in

the Topkapi Museum was only one from an original map, which included

the Seven seas, (Mediterranean,

India, Persia, East Africa, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Red Sea),

that's the world in its vastness, and at a

very early date. The search for the other parts has remained

fruitless.17

Kitab I-Bahriye

The matter of Piri Reis' World Map, however exciting, can be the

object of a subsequent study; here, focus

will be placed on his Kitab i-Bahriye. Kahle, again, pioneered the

study of this work in two volumes.18 His

version is in German only, but there have been some very good

contributions to the subject by Soucek most

of all.19 Mantran also brought his contribution, looking at the

Kitab i-Bahriye's description of the coasts of

Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia and France.20

Esin made a good task of the

Tunisian coast,21 but on this latter

country, it is Soucek's account which really gives most

satisfaction.22 There are a few Italian contributions

by Bausani devoted to the Italian coast,23 and of specific parts of

it, the Venetian coast, the Adriatic and

Trieste.24 The Indian Ocean, too, is subject of interest.25

And

Goodrich informs that the Turkish Ministry of

Culture and Tourism has recently (1988-91) published a four volume

book of such Kitab.26 It includes a

colour facsimile of the said manuscript, each page being a

transliteration of the Ottoman text

into the Latin

alphabet, a translation into modern Turkish, and one into English.27

Kitab I-bahriye has also aroused the

interest of archaeologists, geographers, historians, linguists.28 into the Latin

alphabet, a translation into modern Turkish, and one into English.27

Kitab I-bahriye has also aroused the

interest of archaeologists, geographers, historians, linguists.28

There are two versions of the Kitab. The first dates from 1521 and

the second from five years later. There

are many differences between the two. The first was primarily aimed

for sailors, the second, on the other

hand, was rather more a piece of luxury; which Piri Reis offered as

a gift to the Sultan. It was endowed

with craft designs, its maps drawn by master calligraphers and

painters, and even seen by wealthy

Ottomans of the sixteenth as an outstanding example of bookmaking.29

For a century or more manuscript

copies were produced, tending to become ever more luxurious, prized

items for collectors and gifts for

important people.30 Its luxury aspect apart, this version also gives

good descriptions of matters of maritime

interest such as storms, the compass, portolan charts, astronomical

navigation, the world's oceans, and the

lands surrounding them.

Interestingly it also refers to the European

voyages of discovery, including the

Portuguese entry in the Indian Ocean and Columbus's discovery of the

New World.31 This version also

includes two hundred and nineteen detail charts of the Mediterranean

and Aegean seas, and another three

of the Marmara Sea without text.32

There are around thirty manuscripts of the Kitab al-Bahriye

scattered all over libraries in Europe. Most manuscripts (two third)

are of the first version. Soucek gives an excellent inventory of the

location and details of both versions,33 amongst which are the

following:

First version:

• Istanbul Topkapi Sarayi, Bibliotheque, ms Bagdad 337

• Istanbul Bibliotheque Nuruosmaniye, ms 2990

• Istanbul Bibliotheque Suleymaniye, ms Aya Sofya 2605

• Bologna, Bibliotheque de l'Universita, collection marsili, ms

3612.

• Vienna, Nationalbibliothek, ms H.O.192.

• Dresden, Staatbibliothek, ms. Eb 389.

• Paris, Bibliotheque nationale, suppl.turc 220.

• London, British Museum, ms. Oriental 4131.

• Oxford, Bodleian library, ms Orville X infra.

• USA, private collection.

2nd version:

• Istanbul, Topkapi sarayi, Bibliothque, ms. Hazine 642.

• Istanbul, Bibliotheque Koprulu Zade fazil Ahmad pasa, ms. 171.

• Istanbul, Bibliotheque Suleymaniye, ms Aya Sofya 3161.

• Paris Bibliotheque nationale suppl. Turc 956.

Nautical instructions in Kitab I-Bayrye

Translation of the

Kitab: The Portulan

Kitab-i balhriye translated by Hess as Book of Sea Lore,34 is what

is commonly known as a portulan, i.e. a

manual for nautical instructions for sailors, to give them good

knowledge of the Mediterranean coast,

islands, passes, straits, bays, where to shelter in face of sea

perils, and how to approach ports, anchor, and

also how provides them with directions, and precise distances

between places.35

It is the only full portolan,

according to Goodrich of the two seas (Mediterranean and Aegean

Seas) ever done, and caps both in text

and in charts over two hundred years of development by Mediterranean

mariners and scholars.36 Whilst

Brice observes that Kitab-I Bahriye provides,

‘the fullest set known

to us of the kind of large scale detailed

surveys of segments of coast which, by means of joining overlaps and

reduction to a standard scale, were

used as the basis for the standard Mediterranean Portolan

outline.' 37

And in his introduction, Piri Reis

mentions that he had earlier designed a map of the world which deals

with the very recent discoveries of

the time, in the Indian and Chinese seas, discoveries known to

nobody in the territory of the Rum.38

He also

gives reasons for making his compilation:39

‘God has not granted the possibility of mentioning all the

aforementioned things (i.e cultivated and ruined places, harbours

and waters around the shores and islands of the Mediterranean, and

the reefs and shoals in the water) in a map since, when all is said

and done, [a map] is a summary. Therefore experts in this science

have drawn up what they call a ‘chart' with a pair of compasses

according to a scale of miles, and it is written directly on to a

parchment.

Therefore only three points can fit into a space of ten

miles, and there are places of less than ten miles. On this

reckoning only nine points will fit into a space of thirty miles. It

is therefore impossible to include on the map a number of symbols,

such as those showing cultivated and derelict places, harbours and

waters, reefs and shoals in the sea, on what side of the

aforementioned harbours they occur, for which winds the harbours are

suitable and for which they are contrary, how many vessels they will

contain and so on.

If anyone objects, saying, ‘Is it not possible to put it on several

parchments?' the answer is that the parchments would become so big

as to be impossible to use on board ship. For this reason,

cartographers draw on a parchment a map, which they can use for

broad stretches of coast and large islands. But in confined spaces

they will a pilot..

And whilst Piri Reis notes that his

Kitab will supply enough good

detail to obviate the need for a pilot, this

passage also shows his familiarity with small scale portolans of the

Mediterranean, his kitab being designed

to overcome their shortcomings.40

The contents of Kitab-I Bahriye are organized in chapters, 132 of

them in the first version, and 210 in the

second. Each is accompanied by a map of the coast or the island in

question. In Harley's, alongside

Soucek's article, are beautiful maps and charts of the island of

Khios, the Port of Novograd, the city of Venice, the Island of

Djerba etc.41 It was, indeed, Piri Reis.s recurrent emphasis that

text and map complement each other.42

In places, Piri Reis follows

his predecessors that include Bartolomoeo della Sonetti (himself

having found inspiring himself in previous Islamic sources). On the

whole, though, Piri Reis brings many improvements.43 The copy at the

Walters Art gallery of Baltimore in the USA (W.658), which includes

sixteen supplemental maps, attracts much focus by Goodrich.44

Description of

the Mediterranean Coasts

Maps

one, two, three and four bear an extraordinary beauty, and map three

(f.40b) World Map in a Double Hemisphere, appears in no other

manuscript. Furthermore, this map, Goodrich observes,45 is very

similar to the ‘Mappe Monde.. of 1724 by Guillaume de L.Isle.46 Map

Four (f.41ª) is the Oval World Map with the Atlantic Ocean in the

Center.

Goodrich also notes47 that a later map (from 1601), Arnoldo di

Arnoldi's two sheet world map, an oval

projection called ‘Universale Descrizione Del Mondo' is almost

exactly the same as Piri Reis..48

The wealth of information in Kitab I-Bahriye is articulated in the

series of articles on the Mediterranean coasts. The French coast ,49

here briefly summarized, includes four maps, and delves on some

important locations such as the city of Nice, or Monaco, which Piri

Reis observes, offers good possibilities for anchorage. Marseilles,

its port and coastline, receive greater focus; and from there, it is

said, French naval expeditions are organized and launched.

The

Languedoc region, from Cape of Creus to Aigues Mortes, is

inventoried in every single detail, too: its coastline, water ways,

ports, distances, and much more. Kitab I-Bahriye thus offering, not

just accurate information to sailors, but also pictures of places of

times long gone to readers and researchers.

The southern shores of the Mediterranean, however, capture even

greater focus. They were the natural

base of the Turks led by Kemal rais, and amongst whom was also Piri

Reis. The description of the Tunisian

coast, in particular, deserves thorough consideration. Mantran's 50

study although adequate is less worthy

than Soucek's, which is here relied upon.51

Soucek uses the term

Tunisia but recognizes that Ifriqyah is

more correct (note 16, p. 132) as the focus stretches from Bejaia (today's

Algeria in the West) to Tripoli

(Libya) in the east. At the time, though, both places were under the

Hafsid dynastic rule.

The Muslims of

North Africa, as a rule, welcomed the Turks not as aliens but as

allies (p. 130.) At the time, the inhabitants

of North Africa were, indeed, under constant threat of attacks by

European pirates, who often came

disguised as Muslims in order to capture Muslims (note 4, p. 161).

Turkish seamen used those southern

shores to rest between their expeditions to the north and to the

West, and often wintered in one of the

harbors or islands, and this is how Piri Reis became familiar with

these shores (p. 130).52 First describing Bejaia, he states that it was a handsome fortress situated on a pine

tree covered mountain slope with one

side on the shore. The city's ruler was called Abdurrahman, related

to the Sultan of Tunis, a family

descendant from Ommar Ibn al-Khatab, he holds (p.149).

He observes

that among all the cities of the

Maghreb, none would offer a spectacle comparable to it. Piri Reis

must have seen the Hammadite palaces

and was so impressed by them before they were destroyed by the

Spaniards when they took the city (note

2 page 160). When the Spaniards, indeed, took the city in 1510, they

forced the population to flee to the

mountains, settled part of it, and razed the rest (p.151).53

Piri

Reis moves onto Jijel and the region around,

noting that it was under the rule of Bejaia (prior to the Spanish

take over), under the protection of Aroudj

Barbarosa (p. 157). Further to the east, his attention is caught by

Stora, (now part of Skikda), its ruined

fortress, and the large river which flows in front of its harbor,

its water, he notes, tasting like that of the

Nile. Before crossing into today's Tunisia, Piri Reis notes the

presence of lions in the Bone (Annaba) region

(p.169), people often falling victims to their hunger.54

Piri Reis

begins his exploration of Tunisia proper with

Tabarka, drawing attention that safe anchorage is on the western

side, where it was navigable, and water

deep enough. South of the island of Calta (Galite), he notes great

danger when southern winds blow. The island, he points out has

exceptionally good quality water ‘tasting of rose-water,. (p.177),

and includes innumerable flocks of wild goats.55 Bizerte, on the

other hand, impresses for its sturdy fortress, its good port for

anchorage, and abundance of fish (p.185).

Further on, at Tunis,

great interest is in its climate, commerce, its rulers and their

rivalries. The city has fifty thousand houses, each ‘resembling a

sultan's palace. (p.197), and orchards and gardens fringe the city.

In each of these gardens, were villas and kiosks, pools and

fountains, and the scent of jasmine overpowering the air. There were

water wheels, too, and so many fruit people hardly paid any

attention to them.

The city was visited by Venetians and

Genoese

traders, their ships loading with goods before departing; their site

of anchorage in the port nine miles in front of the city (p.197).

The harbor of Tunis itself is a bay which opens toward the north,

and anchorage, he points out, is seven fathoms deep, the bottom

even, and the holding ground good. Further safety of the port is

secured from enemy fleets by the means of a tower with a canon

guarding it (p.199).

To Cape Cartage, also called cape Marsa,

uninterrupted anchorage is secure, and ships can winter all over the

ports. Danger lies, however, in the vicinity of the island of Zembra,

which is exposed most particularly to southerly winds, whilst rocks

often covered by water (p 201) can be very treacherous. Along the

Hammamet coast, the sea has shallow waters, an even bottom and white

sand. The depth in the open sea, one mile offshore, is four to five

fathoms. (p. 219).

Continuing to Sousse, he points to the large

fortress on the coast facing the North east; in front of it is a

harbor built by ‘infidels.; a man made breakwater, as in the Khios

harbor, protecting it on the outer side. Water, however, is too

shallow for large vessels (p.221). The island of Kerkena offers

excellent anchorage conditions regardless of the severity of the sea

storms; hence an ideal place for wintering (p.235). The same goes

about Sfax. Around Kerkenna, however, he notes, is the constant

threat of European pirates, especially where waters are deep enough

to allow the incursion of their large boats.

The island of Djerba, of all places, is what attracts most attention

(pp 251-267). Piri Reis goes into the

detail of its people, history, customs, economy, and, of course, of

the sailing conditions close and around

the island, including anchorage, nature of currents, tides, and

risks to sailors.

The focused attention on

Djerba is the result of his earlier experiences, when, with his

uncle Kemal, he conducted rescues of Muslim

and Jewish refugees as they were being cleansed out of Spain

following the Christian Re-conquest.56 Now

entering Libya, he is focus falls on Tripoli (pp. 273-285), its

history, commerce, and its thriving port. He

indicates how to sail there using a mountain as landmark.

Anchorage

at the city port is good, he notes,

three islets on the northern side of the harbor, cutting down the

wind velocity. By that time he is describing

the city, though, it had already fallen into Spanish hands,

something that aggrieved him so much. It was

the loss of the place, of course, that of fellow companion seamen,

and above all the destruction of the city

fortress that compounded such grief.

He notes (p.273) that,

in the Maghreb, no fortress was as handsome

as Tripoli's, all its towers and battlements as if cast from bee's

wax, and the walls painted in fresh lime. The

fortress had fallen on July 25, 1510; and so much joy there was in

Spain as in the rest of Christendom, that

Pope Julius II went on a procession of thanks giving.57

References

1 See For instance:

-M Longworth Dames: The Portuguese and Turks in the Indian Ocean in

the 16th century in Journal of the

Royal Asiatic Society, 1921, pp 1-28.

-D.Ross: The Portuguese in India and Arabia between 1507 and 1517,

in Journal of the Royal Asiatic

Society 1921, pp 545-62.

-D. Ross The Portuguese in India and Arabia 1517-38; in Journal of

the Royal Asiatic Society, 1922; pp

118.

2 A.C. Hess: The Evolution of the Ottoman Seaborne Empire in the Age

of Oceanic Discoveries, 1453-1525;

The American Historical Review,Vol 75, 1969-70, pp 1892-1919, at p.

1892.

3 Ibid.

4 W.Brice, and C. Imber: Turkish Charts in the Portolan Style, The

Geographical Journal, 144 (1978); pp

528-529 at p. 528.

5 Ibid.

6 A.C. Hess: The evolution, op cit, p. 1911.

7 T.D. Goodrich: The Ottoman Turks and the New World; Wiesbaden ,

1990.

8 F. Babinger: Piri Reis, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, first edition

(1913-30), vol vi; Leiden. E.J. Brill, pp 10701

9 S. Soucek: Piri Reis, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, New edition,

1995, Vol VIII, Leiden, Brill, pp 308-9.

10 S. Tekeli: ‘Piri Reis. in Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol

10; Editor C.S. Gillispie, Charles Scribner's

Sons, New York, 1974, pp 616-9.

11 S.Soucek: A Propos du livre d.instructions nautiques de Piri

Reis, Revue d.Etudes Islamiques, Vol 41, pp

241-55, at p. 242.

12 P. Khale : Die verschollene Columbus-Karte von 1498 in einer

turkishen Weltkarte von 1513, Berlin, 1933.

In English: P. Kahle: The Lost map of Columbus.

13 Ibid; introduction.

14 C. Hapgood: Maps of the Ancient sea Kings, Philadelphia, 1966.

15 Ibid, p.

16

J.B. Harley and D. Woodward: The History of Cartography, (vol two,

book one: cartography in the

traditional Islamic and South Asian societies;) The University of

Chicago Press, Chicago London, 1992.

17 P. Kahle: The lost, op cit, p.4.

18 P. Kahle: Piri Reis, Bahriye, Berlin 1926, 2 vols.

19S. Soucek: A propos, op cit.

-S. Soucek: Islamic Charting of the Mediterranean; in J.B. Harley

and D. Woodward edt: History, op cit, vol

2, book one, pp 263-92.

20 Robert Mantran: La Description des cotes de l.Algerie dans le

Kitab-I Bahriye de piri Reis, in Revue de

l.Occident Musulman (ROM), Aix en Provence, Vol 15-16, 1973; pp

159-68.

- R. Mantran: La Description des cotes de la Tunisie dans le Kitab I-Bahriye

de Piri Reis, ROM, 23-24

(1977), pp 223-35.

- R. Mantran: Description des cotes Mediterraneene de la France dans

le Kitab I Bahriye de Piri Reis, ROM,

vol 39 (1985); pp 69-78.

-R. Mantran: La Description des cotes de l.Egypte de Kitab I-Bahriye:

Annales Islamologiques, 17, 1981 pp.

287-310.

21 E. Esin: La Geographie Tunisienne de Piri Reis, in Cahiers de

Tunisie, 29, (1981), pp. 585-605.

22 S.Soucek: Tunisia in the Kitab-I Bahriye of Piri Reis, Archivum

Ottomanicum, Vol 5, pp 129-296.

23 Bausani A: L.Italia nel Kitab I-Bayriye di Piri Reis, Il Vetro,

23 (1979), pp 173-96.

24 Bausani A: Venezia e l.Adriatico in un portolano Turco, Venezia e

l.Oriente a cura di L.Lanciotti; Florence:

Olschki, 1987, pp 339-52.

Bausani. A: La Costa Muggia-Triesto-Venezia nel portolano (1521-27)

di Piri Reis, Studi Arabo-Islamici…

a cura di C. Sarnelli Lergua. Naples: Istituto Universitario

Orientale, 1985, (1988); pp 65-9.

25 Allibert. C: Une Description Turque de l.Oceon Indien au XVIem

Siecle: L.Ocean indien Occidental dans le

Kitab-I Bahriye de Piri Reis; Etudes Ocean Indien, 10 (1988); pp

9-51.

26 Thomas.D. Goodrich: Supplemental maps in the Kitab-I bahriye of

Piri Reis, in Archivum Ottomanicum,

Vol 13 (1993-4), Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp 117-35.; at p. 119.

27 Kitab-I Bahriye, Piri Reis, 4 vols, ed., Ertugrul Zekai Okte,

trans, Vahit Cabuk, Tulay Duran, and Robert

bragner, Historical research Foundation-Istambul Research Centre

(Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism

of the Turkish Republic, 1988-91)

28 P. Kahle: the Lost, op cit, p,

2

29 T.Goodrich: Supplemental, op cit, at p.116.

30 Ibid, p. 117.

31 S. Soucek: Islamic Charting, op cit, at p. 272.

32 T. Goodrich: Supplemental, op cit, p.117.

33 A. Soucek,, A propos, op cit, pp 244-5.

34 A.C. Hess: The Evolution, op cit.

35 S. Soucek: A propos, op cit, pp 242.

36 T. Goodrich: Supplemental, op cit, at p.117.

37 W. Brice: Early Muslim Sea-Charts, in The Journal of the Royal

Asiatic Society, 1977, pp 53-61, at p.56.

38 P. Kahle: The Lost, op cit, p. 2.

39 Derived from W.Brice-C. Imber: Turkish Charts, op cit, p 528.

40 Ibid, p.529.

41 S. Soucek: Islamic, op cit,, pp 277-80.

42 Ibid at 277.

43 See fig 1 in W. Brice: early Muslim sea-charts, op cit, at p. 57

44 T.Goodrich: Supplemental, op cit, p. 120.

45 T.Goodrich, Supplemental, op cit, p.122.

46 See R.V. Tooley: French mapping of America, London: Map

Collector.s Circle, 1967.

47 T.Goodrich: Supplemental, op cit, p.122.

48 See Rodney W.Shirley: The Mapping of the World, Early Printed

World maps, 1472-1700; London; The

Holland Press, 1984, no 228 and plate 180.

49 R.Mantran: Description des cotes Mediterranneenes de la France,

op cit.

50 R. Mantran: La Description des cotes de la Tunisie. op cit.

51 S.Soucek: Tunisia in the Kitab-I Bahriye of Piri Reis, Archivum

Ottomanicum, Vol 5, pp 129-296.

52

With respect to this ‘Tunisian. coast, Soucek notes, it is the first

version of the Kitab which is much

richer than the second.

53 Bejaia was to be retaken forty five years later, in 1555 by Salah

Reis, beylerbey of Algiers, but following

the Spanish entry, it never regained its former glory.

54 In 1891, the French killed the last lion of North Africa between

Bone and Bizerte (Tunisia) (Note 5, p.

180. Source in Soucek: L. Lavauden: La Chasse et la faune

cynegetique en Tunisie, Tunis, 1924, p. 9.

55 That is until the French exterminated them all (Lavauden, op cit,

pp 18-19.)

56 S. Soucek: Islamic Charting, op cit, p 267.

57

Note 8, p. 287 in Soucek., Source Sanuto Diarii, v, fol.109.

The city was retaken from the Spaniards in 1551 by Sinan Pasha and

Turgut.

Bibliography

-C.Allibert. C: Une Description Turque de l.Ocean Indien au XVIem

Siecle: L.Ocean indien Occidental dans le

Kitab-I Bahriye de Piri Reis; Etudes Ocean Indien, 10 (1988); pp

9-51.

-F. Babinger: Piri Reis, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, first edition

(1913-30), vol vi; Leiden. E.J. Brill, pp 1070

1.

-A. Bausani: L.Italia nel Kitab I-Bayriye di Piri Reis, Il Vetro, 23

(1979), pp 173-96.

-A.Bausani: Venezia e l.Adriatico in un portolano Turco, Venezia e

l.Oriente a cura di L.Lanciotti; Florence:

Olschki, 1987, pp 339-52.

-A.Bausani: La Costa Muggia-Triesto-Venezia nel portolano (1521-27)

di Piri Reis, Studi Arabo-Islamici…

acura di C. Sarnelli Lergua. Naples: Istituto Universitario

Orientale, 1985, (1988); pp 65-9.

-W.Brice, and C. Imber: Turkish Charts in the Portolan Style, The

Geographical Journal, 144 (1978); pp

528-529.

-W. Brice: Early Muslim Sea-Charts, in The Journal of the Royal

Asiatic Society, 1977, pp 53-61.

-E. Esin: La Geographie Tunisienne de Piri Reis, in Cahiers de

Tunisie, 29, (1981), pp. 585-605.

-T.D. Goodrich: The Ottoman Turks and the New World; Wiesbaden ,

1990.

-Thomas.D. Goodrich: Supplemental maps in the Kitab-I bahriye of

Piri Reis, in Archivum Ottomanicum, Vol

13 (1993-4), Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp 117-35.

-C. Hapgood: Maps of the Ancient sea Kings, Philadelphia, 1966.

-J.B. Harley and D. Woodward: The History of Cartography, (vol two,

book one: cartography in the

traditional Islamic and South Asian societies;) The University of

Chicago Press, Chicago London, 1992.

-A.C. Hess: The Evolution of the Ottoman Seaborne Empire in the Age

of Oceanic Discoveries, 1453-1525;

The American Historical Review,Vol 75, 1969-70, pp 1892-1919.

-P. Khale : Die verschollene Columbus-Karte von 1498 in einer

turkishen Weltkarte von 1513, Berlin, 1933.

In English: P. Kahle: The Lost map of Columbus.

-P. Kahle: Piri Reis, Bahriye, Berlin 1926, 2 vols.

-M Longworth Dames: The Portuguese and Turks in the Indian Ocean in

the 16th century in Journal of the

Royal Asiatic Society, 1921, pp 1-28.

-Kitab-I Bahriye, Piri Reis, 4 vols, ed., Ertugrul Zekai Okte,

trans, Vahit Cabuk, Tulay Duran, and Robert

bragner, Historical research Foundation-Istambul Research Centre

(Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism

of the Turkish Republic, 1988-91).

-L. Lavauden: La Chasse et la faune cynegetique en Tunisie, Tunis,

1924.

-R. Mantran: La Description des cotes de l.Algerie dans le Kitab-I

Bahriye de piri Reis, in Revue de

l.Occident Musulman (ROM), Aix en Provence, Vol 15-16, 1973; pp

159-68.

-R. Mantran: La Description des cotes de la Tunisie dans le Kitab I-Bahriye

de Piri Reis, ROM, 23-24 (1977),

pp 223-35.

-R. Mantran: Description des cotes Mediterraneene de la France dans

le Kitab I Bahriye de Piri Reis, ROM,

vol 39 (1985); pp 69-78.

-R. Mantran: La Description des cotes de l.Egypte de Kitab I-Bahriye:

Annales Islamologiques, 17, 1981 pp.

287-310.

-D.Ross: The Portuguese in India and Arabia between 1507 and 1517,

in Journal of the Royal Asiatic

-D. Ross The Portuguese in India and Arabia 1517-38; in Journal of

the Royal Asiatic Society, 1922; pp

118.

-Sanuto Diarii, v, fol.109.

-Rodney W.Shirley: The Mapping of the World, Early Printed World

maps, 1472-1700; London; The Holland

Press, 1984, no 228 and plate 180.

-S. Soucek: Piri Reis, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, New edition, 1995,

Vol VIII, Leiden, Brill, pp 308-9.

-S.Soucek: A Propos du livre d.instructions nautiques de Piri Reis,

Revue d.Etudes Islamiques, Vol 41, pp

241-55.

-S. Soucek: Islamic Charting of the Mediterranean; in J.B. Harley

and D. Woodward edt: History, op cit, vol

2, book one, pp 263-92.

-S.Soucek: Tunisia in the Kitab-I Bahriye of Piri Reis, Archivum

Ottomanicum, Vol 5, pp 129-296.

-S. Tekeli: ‘Piri Reis. in Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol

10; Editor C.S. Gillispie, Charles Scribner's

Sons, New York, 1974, pp 616-9.

-R.V. Tooley: French mapping of America, London: Map Collector.s

Circle, 1967.

|

into the Latin

alphabet, a translation into modern Turkish, and one into English.27

Kitab I-bahriye has also aroused the

interest of archaeologists, geographers, historians, linguists.28

into the Latin

alphabet, a translation into modern Turkish, and one into English.27

Kitab I-bahriye has also aroused the

interest of archaeologists, geographers, historians, linguists.28