|

Chapter 7

THE HONORARY ARYAN BRETHREN

"Contrary to the widely held view, the United States

may have known about the Japanese project before the end of the war,

and this information might have influenced President Harry Truman's

decision to use the bomb on Japan.1

"... when UN forces had been at Hungnam in connection

with the retreat from Chosin, a mysterious installation in the mountains

around it had been discovered. "2

Robert K. Wilcox

Japan's Secret War

An ancient Japanese legend has it that the Japanese people

are descended from a blonde haired blue eyed race that came from the stars,

a legend remarkably similar to the doctrines that percolated in the secret

societies that fostered and mid-wifed the Nazi Party into existence in

Germany between the World Wars. Nor did this legend play a small part

in the history of World War Two, for it was partly because of its mere

existence that Hitler could proclaim the Japanese "honorary Aryans"

and conclude the incorporation of Japan into the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis

without contradicting Nazi Party racial ideology.

This was in no small

part due to the Japanese ambassador in Berlin's diplomatic skill in pointing

out this little known fact of Japanese legends to the Germans. Of course,

there were pressing military and political reasons for Italy and Germany

to conclude an alliance with Japan, but for the race and ideology obsessed

Nazi government, so much the better if the Japanese had some sort of Nordic-Aryan

connection, no matter how tenuous that might be. An early and continuous

problem for the three Axis partners was to arrange the transfer of technology

and raw materials from Europe to the Far East. Most transfers occurred

via U-boats or Japanese submarines, though both Germany and Italy undertook

long range, and militarily quite

risky, flights to Japan as well.

1 Robert

K. Wilcox, Japan's Secret War: Japan's Race against Time toBuild is Own

Atomic Bomb, p. 18.

2 Ibid., p. 211.

The Italians, for example, mounted such a flight with a Savoia

Marchetti S 75 GA during 1942, ostensibly for the purpose of supplying

the Italian embassy in Tokyo with copies of new Italian code books, since

the Commando Supremo had concluded that the Allies had broken Italian

codes.3 As the war progressed, the Germans

found themselves increasingly trading their high technology for very little

in return other than the prospect of stiffening Japanese resistance and

perhaps drawing American force to the Pacific and lessening pressure on

the Reich. And the Japanese, their industry hard-pressed to maintain pace

with American and British technological developments, were always very

eager, and very specific, in their demands for high technology from their

Aryan brethren.

Even the conventional military technology transfers

form Germany to Japan are staggering enough. By 1944 Japan had requested

and received either working models or full production designs for the

following:

-

German techniques for manufacturing cartridge steel for large

gun barrel linings;

-

Finished artillery pieces;

-

105 and 128 mm heavy anti-aircraft (FLAK) guns;

-

the 75 and 88 mm field pieces and anti-tank guns;

-

the Wurzburg radar system;

-

750 ton submarine pressure hulls;

-

the PzKw Via Tiger I tank;

-

The Focke Wulfe 190 fighter;

-

The Henschel 129 tank-busting aircraft;4

3

Dr. Publio Magini, Military History Quarterly,

Summer 1993. I am very grateful to Frank Joseph for uncovering and sharing

this information with me. The updating of Italian code books would be

a pressing enough matter for the Italians to undertake such a flight.

4

This rather odd-looking twin engine aircraft

had a bulbous cupola slung beneath the nose of the main fuselage, in which

was mounted a 75mm automatically reloading high velocity anti-tank gun

projecting from its nose. It was a deadly and efficient tank-busting airplane

used with great effectiveness on the Eastern Front, curiously resembling

a similar ground assault aircraft in the modern American arsenal, the

A-10 "Warthog."

-

The Heinkcl He 177 heavy bomber;

-

The Messcrschmitt 264 long-range Amerikabomber;

-

The Messerschmitt 262 jet fighter;

-

The Messerschmitt 163 rocket-powered fighter;

-

The Lorenz 7H2 bombsight;

-

The B/3 and FUG 10 airborne radars; and perhaps significantly,

-

Twenty-five pounds of "bomb fuses."5

5 Joseph Mark Scalia, Germany's Last Mission

to Japan: The Failed Voyage of the U-234, pp. 7-9.

Fortunately for American and Commonwealth forces in the

Pacific theater, these weapons never saw full scale production by the

Japanese. What is intriguing is the last item. Why bomb fuses? Surely

the Japanese, who had been raining bombs all over China, Indochina, Burma,

and the Pacific knew how to fuse a conventional bomb. The request suggests

that the fuses were of a sophistication beyond the capabilities of Japanese

industry. And why a request for heavy bombers so close to the end of the

war, at least one of which was reputedly capable of ultra-long-range flight

and heavy payload?

A. Strange Rumors

As with the end of the war in Europe, the end of the

Pacific war carried with it the odd rumor or two, some of which managed

to appear in short articles in the Western Press, before the curtain of

the Allied Legend slammed down to hide their implications from view. Robert

K. Wilcox, in a book that may well in retrospect be the first book on

the German bomb project from a revisionist perspective, Japan's Secret

War, revitalized these reports and rumors:

Shortly after World War II had ended, American intelligence

in the Pacific received a shocking report: The Japanese, just prior to

their surrender, had developed and successfully test-fired an atomic bomb.

The project had been housed in or near Konan (Japanese name for

Hungnam),

Korea, in the peninsula's North. The war had ended before this weapon could be used, and the plant where it had

been made was now in Russian hands.

By the summer of 1946 the report was public.

David Snell,

an agent with the Twenty-fourth Criminal Investigation Detachment in Korea...

wrote about it in the Atlanta Constitution following his discharge.6

6

Wilcox,

op. cit, p. 15.

Snell's source for the allegation was a Japanese officer

returning to Japan. The officer informed him that he had been in charge

of security for the project. Snell, paraphrasing the officer in his article,

stated:

In a cave in a mountain near Konan men worked, racing

against time, in final assembly of "genzai bakudan," Japan's

name for the atomic bomb. It was August 10, 1945 (Japanese time), only

four days after an atomic bomb flashed in the sky over Hiroshima and five

days before Japan surrendered.

To the north, Russian hordes were spilling into Manchuria.

Shortly after midnight of that day, a convoy of Japanese trucks moved

from the mouth of the cave, past watchful sentries. The trucks wound through

valleys, past sleeping form villages.... In the cool predawn, Japanese

scientists and engineers loaded genzai bakudan aboard a ship at Konan.

Off the coast, near an islet in the sea of Japan, more

frantic preparations were under way. All that day and night, ancient ships,

junks and fishing vessels moved into the anchorage.

Before dawn on August 12, a robot launch chugged through

the ships at anchor and beached itself on the islet. Its passenger was

genzai bakudan. A clock ticked.

The observers were 20 miles away. The waiting was difficult

and strange to men who had worked relentlessly so long, who knew their

job had been completed too late.

The light in the east, where Japan lay, grew brighter.

The moment the sun peeped over the sea there was a burst of light at the

anchorage, blinding the observers, who wore welder's glasses. The ball

of fire was estimated to be 1,000 yards in diameter. A multicolored cloud

of vapors boiled toward the heavens, then mushroomed in the atmosphere.

The churn of water and vapor obscured the vessels directly

under the burst. Ships and junks on the fringe burned fiercely at anchor.

When the atmosphere cleared slightly the observers could detect

several vessels had vanished. Genzai bakudan in that moment had matched

the brilliance of the rising sun to the east. Japan had perfected and

successfully tested an atomic bomb as cataclysmic as those that withered

Hiroshima and Nagasaki.7

There are a number of things to note about this account.

How had Japan, hard-pressed for even conventional military technology,

pulled off this feat of testing an atom bomb of the same approximate yield

as Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Where did they get the enriched uranium for

the weapon? Moreover, the Japanese had tested their bomb only three days

after the plutonium "Fat Man" fell on and obliterated Nagasaki.

Small wonder then, that the Japanese cabinet debated whether or not to

surrender. This important fact, in conjunction with Wilcox's startling

revelations, will serve as the basis for further speculation in a moment.

Finally, the test itself suggested that the Japanese envisioned deploying

the weapon against naval targets. What possible thoughts may have been

going through the Japanese cabinet's surrender debate? Possible clues

lie in the nature of the Japanese program itself, and its significant

reliance on technology transfers from Germany.

The chief physicist involved in the Japanese project

was Yoshio Nishina, a "colleague of Niels Bohr."8

It was Nishina who in fact headed the Japanese army team that investigated

Hiroshima after the bombing of that city.9

The reports of the Japanese test at Konan were a steady source of consternation

and mystification to American intelligence units in occupied Japan after

the war, for unlike its obsession with the German bomb program, Allied

intelligence consistently placed the Japanese far behind, as conducting

only theoretical studies, and maintaining that the Japanese "had

neither the talent nor the resources to make a bomb."10

7

Wilcox,

op. cit., p. 16.

8 Ibid., p. 17, referencing an article in the

January 1978 edition of Science magazine.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

Resources Japan may have lacked, but there was no lack of talented physicists who understood bomb physics.

In any case the reports caused enough concern for the American occupying

forces to send several intelligence teams throughout Japan to destroy

its cyclotrons, of which there were no less than five, and presumably

more!11 This curious fact raises a question. What were the

Japanese doing with that many cyclotrons? Could they have perhaps been

given the secrets of Baron Manfred Von Ardenne's method of mass spectrograph

separation and enrichment of uranium 235? Or did the Japanese physicists,

like their German and American counterparts, come to the realization that

the cyclotron afforded a method for isotope enrichment? Both are possible,

and the latter is probable.

11

Wilcox,

op. cit., pp. 17, 192.

B. Strange Industrial Complexes: Kammler Revisited,

Noguchi Style

Further confirmation of a Japanese atom bomb test led

Wilcox to connect Nishina to a Japanese industrialist named Noguchi. Searching

through American declassified records, Wilcox quickly concluded that,

"subsequent

directives in the same boxes ordered reinvestigations in 1947 and 1948

of Japanese wartime atomic research, indicating that (American intelligence)

still did not know exactly what had happened. In fact, (it) was continually

ordering reinvestigations of Japanese wartime atomic research and discovering

new facts at least up until 1949, according to additional documents that

I found."12

Then Wilcox struck a

very rich vein:

Box 3 of Entry 224 yielded a high mark of my two days

at Suitland:13

an interrogation of a former engineer at the Noguchi Konan

complex, Otogoro Natsume, conducted on October 31, 1946. "Subject"

of the interrogation was listed as "Further questioning the newspaper

story about atomic bomb explosion in Korea."

12

Ibid., p. 222.

13

"Suitland" is Wilcox's nickname for the US National

Archives

In attendance were head(sic) of the Science and Technology Division, Dr.

Harry Kelly; an interpreter, "T/4

Matsuda," and a "Mr. Donnelly,"

identified only as "5259 TIC." He apparently was some sort of intelligence officer and, judging from their

questions, the interrogators had more information about the Konan-Hungnam

story that was in the newspaper.

Natsume, a chemical engineer, according to the interrogation,

had been imprisoned by the Russians and then released to run a Konan plant

until he escaped "on a small sailing boat" in December 1945.

He told the investigators he'd heard the rumors about the atomic bomb

explosion at Konan but knew nothing about it. According to the transcript,

the following exchange then ensued:

Kelly: "Did any of the plants have accidents during

the war?"

Donnelly: "We haven't actually found anything concrete.

Last few days we have been talking with people here in and around Tokyo

and asking them about report(s) of decomposition of hydrogen peroxide

and asking them if they knew about it or which plant it was."

Kelly: "Did any of the plants have accidents during

the war?"

(Natsume through Matsuda): "There were none."

Donnelly: "Ask him if he knows anything about the NZ plant

making hydrogen peroxide."

Matsuda: "He says that he heard about

the factory but it was under the Navy and highly secret. He had never

been in it."

Kelly: "What was the name of the plant?"

Matsuda: "He says just NZ plant."

Donnelly: "ask him what NZ plant made and what does NZ mean?"

Matsuda: "He doesn't know." A few more questions about the ownership

and location of the plant, then:

Kelly: "About how many chemists worked up there?"

Matsuda: "He says there are so many classes of chemists.

Do you mean University Graduate?"

Kelly: "yes."

Matsuda:

"He says that there are two factories under management of this company - one in Konan and one in Honbu. There

are about 700 chemists altogether (approximately 300 at Konan)."

In a lengthy exchange, Natsume indicated that most of

the scientists, engineers, and workers at Konan were arrested and then

later released to go back to work. But six key technical people from NZ,

whom he later named, were not released and he had "no idea"

what the Russians were doing with them except they were being held in

the "secret plant."

Kelly: "Has he got any idea as to how we can get

these secret plans?"

Matsuda: "The six men mentioned are the only ones

who knew much about the secret plant."14

As we shall see momentarily, perhaps the most significant

thing about this interrogation is the date, October 31, 1946. It is also

significant that the bulk of the scientists involved appear to have been

chemists. Finally, as is apparent from the interrogation, the plant or

plants at Konan were of significant size.

So what was the Konan complex? To reconstruct it requires

a similar process to that used in examining the German uranium enrichment

program. The transcript connects the Konan complex and a Japanese industrialist

named Noguchi.

Jun Noguchi had built the huge Japanese complex of factories

that nestled about the Yalu, Chosin, and Fusen rivers. The latter two

rivers had been dammed by Noguchi to supply the enormous electrical power

needed by his factories. "Together the three rivers delivered more

than 1 million kilowatts of power" to the complex.15

This was for the time a prodigious amount of electricity, especially

in view of the fact that all of Japan produced no more than 3 million.16

Begun in 1926 in a deal struck with the Japanese Army Noguchi's Konan

empire expanded along with Japan's imperial appetites.

So, like the I.G. Farben "Buna" plant at Auschwitz,

we note already two key ingredients are present at Konan: large electrical

power production infrastructure, and proximity to large amounts of water.

Konan, in fact, was the largest industrial complex in all of Asia, and

relatively sheltered and even unknown to Allied bomber and the intelligence

committees that prepared their targets lists.17

But there is more.

Declassified documents noted that Konan was also near

uranium ore deposits.

"This was the logical place for an end-of-the-

war atomic bomb project."18

14 Wilcox, op. cit, pp. 222-224.

15 Wilcox, op. cit., p.63.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid., p. 27.

18 Ibid.

Moreover,

as Wilcox discovered, "More digging...turned up a lengthier summary."

Dated May 21, 1946 and originating within the US Army's chief of staff

office in South Korea, it stated:

Of increasing interest have been recent reports dealing

with an apparent undercover research laboratory operated by the Japanese

... at ... Hungnam.... All reports agree that research and experiments

on atomic energy were conducted.... The two chief scientists were Takahashi,

Rikizo and Wakabayashi, Tadashiro.... The recent whereabouts of these

two individuals is not known, inasmuch as they were taken into custody

by the Russians last fell.

However, before their capture they are reported

to have burned their papers and destroyed their laboratory equipment....

Some reports... say... the Russians were able to remove some of the machinery.

Further reports stated that the actual experiments on atomic energy were

conducted in Japan, and the Hungnam plant was openedfor

the development of the practical application of atomic energy to a bomb

or other military use. This section of the ... plant ... was always heavily

guarded.... These reports received separately are surprisingly uniform

as to content. It is felt that a great deal of credence should be attached

to these reports as summarized.19

19

Wilcox,

op. cit, p. 28.

We may now speculate as to the real significance of these

US Army intelligence reports in the light of subsequent events.

Clearly, the US Army is taking seriously allegations

of a Japanese atom bomb project based in the northern Korean Peninsula,

very close in fact, to the international border with China, and scene

of one of the Korean War's bloodiest battles. At the Chosin Reservoir,

General of the Armies Douglas MacArthur had been dealt a significant defeat

and was forced to retreat.

Indeed, after his celebrated landing at

Inchon,

MacArthur had relentlessly driven his troops northward in a classic blitzkrieg

style campaign, designed in part to seize the Yalu River crossings, crucial

to any further operations in China, as well as for defense against

any Chinese invasion of the peninsula. And the Chosin Reservoir, and hence

Noguchi's vast Konan complex, was also a prime military target. With MacArthur's

insubordination and the subsequent Chinese entry into the war, Truman fired

MacArthur. So

goes the standard history.

But could the real motivations for MacArthur's lightening

dash up the peninsula toward Chosin alter the Inchon landings in fact

have been based on a very different, and highly secret, agenda of military

objectives? Given the US Army's own intelligence memoranda concerning

the Konan complex and Russian activities it seems all too likely. And

this in turn may mean that the real motivations for his subsequent firing

by Truman may also lie in what he uncovered there: certain knowledge of

the extent, capabilities, and actual achievements of the Japanese scientists

and engineers working on the genzai bakudan.

But what would have been so sensitive about the Japanese

atom bomb project, beyond its actual achievements? To answer this question,

we must speculate once again. What isotope separation and enrichment methods

were known to the Japanese? What did physicist Nishina and his team of

scientists finally rely on? Like them German counterparts, the Japanese

knew that the ultra-centrifuge was the simplest path, at least in theory,

toward the uranium bomb. But Japanese scientists calculated the needed

revolutions-per-minute of such a device to be between 100,000 and 150,000

rpms. The United States itself, because of the difficulties in designing

turbines of this speed, decided to forego enrichment via this

20 process.

At this point, Wilcox's reconstruction begins to run

into a bit of trouble, for the Japanese, he reports, were able to design,

and apparently to build, a large ultra-centrifuge.21

20 Wilcox, op. cit, p. 119.

21 Ibid., p. 120.

Their only problem, according to Wilcox, was a large enough supply or

uranium. However, there is a significant weakness in this construction,

for the Japanese, it will be recalled, had to request German assistance

in the design and production of jet engines, a request that led not only

to the exchange of blueprints for the Messerschmitt 262, the world's first

operational jet fighter, but of technicians able to show the Japanese

the necessary production methods and tolerances to construct such high

speed turbines operating under the stress of tremendous heat. In other words, while

Japanese theoretical capabilities were not lacking

at that time, they did lack certain industrial expertise which only the

Germans possessed. Moreover, as we have already seen, the centrifuge idea

had originated and been developed by the Germans. So if the Japanese

successfully designed and built a large ultra-centrifuge, it would seem

likely that German assistance was involved at some point.

The other method, a cheaper method and certainly one

well within Japanese wartime industrial capability, and one taken to extremely

large size by them, was very much a German device.

What the Nishina group finally did settle on was a process

called thermal diffusion. This had been one of the first isotope separation

processes devised. But until it was perfected by two German scientists,

Klaus Clusius and Gerhard Dickel, in 1938, it had not been practical.

Stated simply, thermal diffusion relied on the fact that light gas moves toward heat. Clusius and Dickel constructed a simple

device consisting chiefly of two metal tubes placed on inside the other.

The inner tube was heated; the outer one was cooled. When the apparatus

was turned on, the lighter U-235 moved to the heat wall; the U-238, to

the cold wall. Convex currents created by this movement sent the U235

upward; the U-238 downward.... At a certain point the U-235 at the top

could be collected, and new gas pumped in. it was a simple and rapid way

to get relatively large concentrations of U-235.22

22

Wilcox,

op. cit, p. 95.

As Wilcox

notes, this process, developed as it was in Germany,

gave the Japanese access to the latest development of this simple and

unusual technology. And as we have already seen, the Germans also deliberately

fabricated an alloy - Bondur - to offset the highly corrosive effects

of uranium gas.

Used in large size and enough quantity - At Auschwitz

and Konan - and perhaps in conjunction with other technologies of enrichment,

Von Ardenne's mass spectrograph adaptations of cyclotrons, it is entirely

feasible that the Japanese also had a highly secret uranium enrichment

project being run near the Konan complex.

So one

may advance the line of speculation further: with the surrender of the

U-234 and its cargo of infrared proximity fuses and their inventor, Heinz Schlicke, and Japan's own request

for "fuses" and plans for German strategic heavy bombers, MacArthur's

troops at the Chosin Reservoir may have uncovered not only evidence of

Japanese progress and eventual testing of a uranium atomic bomb but they

may have uncovered further evidence of the success of the program that

lay behind it: Nazi Germany's. Indeed, the fuses point to a possible plutonium

bomb project underway in both countries.

And so we return to the decision of the Japanese cabinet,

and speculate further. If the Japanese government knew of the German program,

they may also have known of the extent of its success Two bombs had fallen,

and according to the translator for Marshal Rodion Malinovsky, another

had fallen but not detonated. In any case, the Japanese were probably

aware that while America's single bomb project may not have been capable

of delivering more bombs within a short span of time, there would have

been no way to estimate how many bombs might have been taken as war booty

from the Germans.

And the failure of the U-234's mission would have told

them that at the minimum, fuses capable of use in a plutonium bomb as

well as a large supply of enriched uranium had fallen into Allied hands.

By August 12, 1945, with the successful test of the Japanese bomb and

the German test of October 1944. the war had gone nuclear.

Thus, if the Japanese had been informed of the successful

test of the German atom bomb in October of 1944, then the debate of the

Imperial Cabinet in Tokyo is understandable. Japan was faced with a potential

rain of atom bombs "of German provenance," to quote Oppenheimer's

curious remark once again. Surrender, ganzai bakudan notwithstanding,

was the logical choice, even for a nation steeped in "proud samurai

traditions of honor."

Perhaps it is significant, in the light of contemporary

problems with a nuclear North Korea, that the Japanese government issued

a strong warning to North Korea that it could arm itself to the teeth

with nuclear and thermonuclear weapons in a heartbeat, and would not hesitate

to do so if threatened.

In this light, perhaps the most significant fact uncovered

by Wilcox is that,

"contrary to the conventional military history

that Japanese atomic efforts were bombed into extinction by spring 1945... the project was continued and heightened even after

the Emperor's August 15 surrender."23

23

Wilcox, op. cit., p. 239.

Wilcox does not elaborate

much farther than this, but the statement raises a

chilling prospect:

How could a Japanese project survive right under the noses of

the occupying American forces? ... and what if it was not only the

Japanese project that survived?

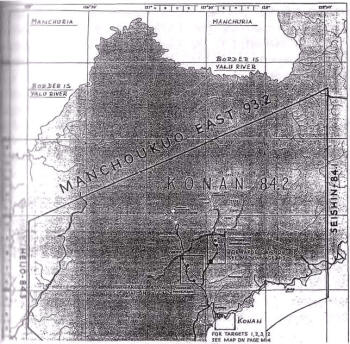

The Konan (Chosin)Region

of North Korea

Back to Contents

|